When I wrote about the first stop on our trip, Ho Chi Minh, I casually mentioned the “frenzy of traffic”. In Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital, it was just out of control. You know things are a problem when on the “Hotel information” sheet left in your room, point number one is “How to cross roads.” “How to cross roads, Australian edition” would read “walk to crossing, wait for traffic to stop, cross road.”

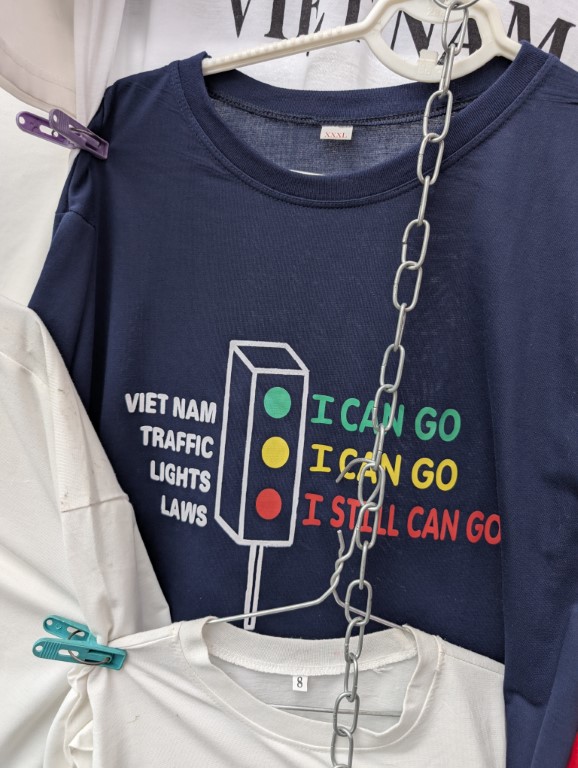

The Vietnam version reads: “Be relaxed and self-confident, pay attention to incoming drivers, keep your speed steadily, and NEVER WALK BACK.” Nobody stops for anyone. Traffic lights and rules are merely recommendations. Motorbikes and scooters are overloaded with people and cargo. We saw a guy riding with a newborn baby in one hand, mobile phone in the other. A guy with a pane of glass under one arm, smoke in the other hand. A guy with TWO WASHING MACHINES. One with eight water dispensers. Boxes and food and birdcages and dogs and bouquets of flowers and balloon displays all being moved around the congested city on motorbikes and scooters, and usually by someone also checking their Instagram.

Somehow though, everyone moves and flows as one. No accidents. No anger. No angry honking…just consistent “hey, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here” beeps. Babies and children are the ones I worry for though, helmet-free and propped up by mum or dad or holding on to the scooter handle bars themselves. Road toll statistics tell of the result of this mad traffic. Around 11,000 people, or 30.6 people per 100,000, die on Vietnam’s roads each year. As a comparison, the number in Australia is 4.5 per 100,000.

This traffic bedlam is then juxtaposed by people doing things in traditional ways that have obviously not changed in generations. Elderly women balance bamboo baskets filled with fruit across their shoulders, their backs bent and burdened by their load. Others squat in shopfronts peeling vegetables, shelling nuts by hand, or grinding herbs using a mortar and pestle.

The hassle of just getting around, and finding a space to walk along congested streets when all of the footpaths are taken over by parked motorbikes; as well as cyclo drivers yelling out “hello madam”, massage spa owners yelling out “madam, massage”, restaurant owners yelling out “madam, eating”; and the incessant heat and humidity of Hanoi just wore us down.

Our hotel Acoustic Hotel and Spa was a luxury experience however, and we were always happy to arrive back to our air-conditioned base and the delightful concierge Martin who would always chat up a storm.

Hanoi felt older and more traditional than Ho Chi Minh. While HCMC was a meeting of the past and the future in a European/Asian fusion; the sprawling laneways of Hanoi’s Old Town seemed like they possibly had not changed in centuries. Streets are organised in trades. You’ll find the jewellers along one street, clothing shops along another, haberdashery on another, electrical goods on another. Shopfronts exploded with red and yellow with paper dragons and fish and lanterns in the strip selling Chinese decorations.

Another inconvenience we noticed more in Hanoi than other parts of Vietnam, was the insistence on paying in cash everywhere, from markets to high-end skybars (which had nothing on the bars in HCMC). There are no signs, no notice, but as you go to pay, it’s “cash only”. And then conveniently, nobody has enough change to give you when you only have big notes.

One of Hanoi’s highlights is its infamous Train Street, which dates back to around 1902, and became Insta-famous in 2018 with travel bloggers posting vision of trains rattling dangerously close to houses and shops through Hanoi’s Old Quarter. While there are barriers up around some sections of the street, if you are invited to sit at a café by the owner, you can be escorted through. I sat comfortably sipping on a fresh coconut, wondering why everyone seemed so chill at being centimetres from a train track. Kittens from a cat café wandered across the tracks. A lady and her dog strolled nonchalantly down the middle.

Then the craziness began. A guy wearing an unofficial polo shirt started blowing a whistle. He shouted at tourists that the train was coming. Locals and their kids kept casually crossing. The guy kept blowing his whistle, shouting and gesticulating, “Train. Train.” We could feel it before we could hear it. It rushed past us and we could have reached out to touch it. People laughed at the ridiculous danger of it all, but were also thrilled by the exhilaration of having a train shuttle past us. The cats did not care.

We spent an evening out in an area of the Old Town lined with clubs, bars and restaurants where we were shouted and grabbed at by owners encouraging us to go into their establishments. Our destination was 1900 Club, a recommendation by one of the tattoo artists in Hue. TBH the vibe was similar to the other club we visited earlier in the trip with small groups of Hanoians who didn’t dance. There was a great lighting rig and DJ set up, and hostesses were being paid to drink and play phone games with men who looked too scared to speak to any other women in the club.

The nation’s hero, Ho Chi Minh’s mausoleum was grand but empty, with his embalmed body being shipped to Russia every year for a few months for “maintenance”.

A Grab (Vietnam’s take on Uber, but a LOT cheaper) took us to Hoan Kiem Lake where we visited the Ngoc Son Temple and two examples of taxidermized Sword Lake Turtles who are only found in this lake, and only 6 currently survive. I love a good folklore tale, and I attempted to piece together the poorly translated sign in the temple about the significance of these turtles. There was something about a turtle offering his claws to make a magical crossbow, and something else about a turtle lending a golden sword to someone else to fight off invaders…but by the time I’d worked all that out I was bored and wanted to go. Plus, those turtle eyes were creepy AF. And I pondered on the importance of turtles to local folklore when moments earlier I had seen tubs of tortoises in the market scratching and clawing at each other attempting to escape. Hmmmm.

We saw goldfish writhing in cramped buckets being sold out the front of another Hanoi temple. We later found out they were sold as “fang sheng” or “life release” where Buddhists purchase and release the fish as an act of compassion. We also saw dead fish floating in the lake nearby. Again. Hmmmmm. At the same temple, tourists wearing singlet tops were approached by vendors with armloads of scarves. “Must cover in temple” they would say, drape the scarf over the tourist, and when the tourist removed the scarf and said “oh, no thanks”, the vendors shouted “you have worn this, you must buy.” The hassling and scamming was rife.

Hanoi felt tired, full, and heaving with people, traffic and rubbish. Houses along the river threw their trash out their windows and it was left lining the waterways, metres thick. We used more plastic bags and bottles in these three weeks than we would in three years back home. If I offered up my own canvas bag, the original plastic bag was just thrown out.

As we stood in 15-minutes of crushed gridlock out the front of a school at their home-time, and students streamed into a street market filled with people and motorbikes and no rules or space, I was left wondering and analysing how things could be made easier, cleaner, and safer for everyone.

But it felt like everyone does things the way they’ve always been done. They takes things day by day, traffic jam by traffic jam, and just get through it.